If you are age 70-1/2 or older and have a traditional IRA, a 401(k), or a SEP IRA, the tax law requires you to take at least a minimum amount – referred to as the required minimum distribution (RMD) – from those accounts each year. The tax code does not allow taxpayers to keep funds in their qualified retirement plans indefinitely. Eventually, assets must be distributed, and taxes must be paid on those distributions. If a retirement plan owner takes no distributions or if the distributions are not large enough to satisfy the amount the law requires, he or she may have to pay a 50% penalty on the amount that is not distributed.

The amount required to be distributed is figured separately for each type of retirement plan. This means, for example, that if more than the required amount is distributed from a traditional IRA, the excess amount can’t be applied to the RMD needed to be distributed from a 401(k) in which the IRA owner has participated.

RMDs must begin in the year when the retirement plan owner attains the age of 70-1/2. The first year’s distribution can be delayed to no later than April 1 of the subsequent year. However, delaying the first distribution means taking two distributions in the subsequent year: one for the age 70-1/2 year and one for the subsequent year, which may or not provide a tax benefit.

For example, individuals who turn age 70 in the first half of 2019 will be 70-1/2 by the end of 2019 and 2019 will be the first year of their RMDs; they can take their first distribution any time in 2019 but can postpone the withdrawal up to no later than April 1, 2020. The next distribution would need to be taken by December 31, 2020. Those turning 70 in the second half of 2019 won’t be age 70-1/2 until sometime in the first six months of 2020, so their first distribution should be in 2020 but could be delayed until April 1, 2021, and their next RMD would have to be by December 31, 2021.

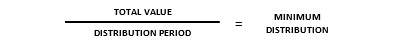

The required withdrawal amount for a given year is equal to the value of the retirement account on December 31 of the prior year divided by the life expectancy from the Uniform Lifetime Table. “Age” is determined by the account owner’s age as of his/her birthday in the relevant distribution calendar year.

Uniform Lifetime Table

| Age | Life | Age | Life | Age | Life | Age | Life | Age | Life |

| 70 | 27.4 | 80 | 18.7 | 90 | 11.4 | 100 | 6.3 | 110 | 3.1 |

| 71 | 26.5 | 81 | 17.9 | 91 | 10.8 | 101 | 5.9 | 111 | 2.9 |

| 72 | 25.6 | 82 | 17.1 | 92 | 10.2 | 102 | 5.5 | 112 | 2.6 |

| 73 | 24.7 | 83 | 16.3 | 93 | 9.6 | 103 | 5.2 | 113 | 2.4 |

| 74 | 23.8 | 84 | 15.5 | 94 | 9.1 | 104 | 4.9 | 114 | 2.1 |

| 75 | 22.9 | 85 | 14.8 | 95 | 8.6 | 105 | 4.5 | 115 | 1.9 |

| 76 | 22.0 | 86 | 14.1 | 96 | 8.1 | 106 | 4.2 | ||

| 77 | 21.2 | 87 | 13.4 | 97 | 7.6 | 107 | 3.9 | ||

| 78 | 20.3 | 88 | 12.7 | 98 | 7.1 | 108 | 3.7 | ||

| 79 | 19.5 | 89 | 12.0 | 99 | 6.7 | 109 | 3.4 |

While an individual may withdraw more than the RMD for a given year, the amount in excess of the RMD can’t be applied to offset the next year’s required distribution. It does, however, reduce the balance in the retirement plan account that will be used to calculate the next year’s RMD.

Retirement plan owners must separately calculate the RMD amount for each qualified retirement account. However, people who have more than one retirement account of the same type don’t have to take a separate RMD for each. They can aggregate and withdraw the entire amount from just one retirement plan of the same type or withdraw a portion from each plan to satisfy their RMD.

Two tables are not illustrated because of their size.

- Joint and Last Survivor Table, which is used to determine RMDs when the sole beneficiary is a spouse who is more than 10 years younger than the plan owner, and

- Single Life Table, which is used for certain beneficiary RMD determinations.

For table values that are not illustrated above, please call the office at (360) 778-2901 for more information.

Roth IRAs – No minimum distributions are required from a Roth IRA while the Roth IRA owner is alive. This means that those who don’t need to utilize their Roth IRA to meet expenses during retirement can leave it untapped for heirs. This exception does not apply to qualified designated Roth 401(k) and 403(b) plans, which are subject to the RMD rules.

Still-Working Exception – An exception to the RMD requirement applies to certain plan participants who are still working. An employee’s required beginning date (RBD) for receiving distributions from a qualified plan is April 1 of the year following the later of the calendar year when the employee reaches age 70-1/2 or the calendar year when he or she retires from employment, with the employer maintaining the plan. The employer’s plan may require the retirement plan participant to begin RMDs under the normal rules, in which case the taxpayer cannot take advantage of the “still working” exception. In addition, this rule does not apply to distributions from IRAs (including those established in conjunction with a SEP or SIMPLE IRA plan) or from qualified plans to more-than-5% owners.

Under-Distribution Penalty – If Jack in the preceding example does not withdraw the $5,859, he would be subject to a 50% penalty (additional tax) of $2,930 ($5,859 x 50%). Under certain circumstances, the IRS will waive the penalty if the taxpayer demonstrates reasonable cause and makes the withdrawal soon after discovering the shortfall in the distribution. However, the hassle and extra paperwork involved in asking the IRS to waive the penalty make avoiding it highly desirable; to do so, always take the correct distribution in a timely manner. Some states also penalize under-distributions.

Even though a qualified plan owner whose total income is less than the return-filing threshold is not required to file a tax return, he or she will still be subject to the RMD rules and can thus be liable for the under-distribution penalty, even if no income tax would have been due on the under-distribution.

IRA-to-Charity Transfers: A provision of the tax code allows taxpayers age 70-½ or over to transfer up to $100,000 annually from IRAs to qualified charities. This provision may provide significant tax benefits, especially for those who would be making large donations to charities anyway.

Here is how this provision, if utilized, plays out on a tax return:

(1) The IRA distribution is excluded from income;

(2) The distribution counts toward the taxpayer’s RMD for the year; and

(3) The distribution does NOT count as a charitable contribution.

At first glance, this may not appear to provide a tax benefit. However, by excluding the distribution, a taxpayer lowers his or her adjusted gross income (AGI), thus allowing him or her to attain certain tax breaks (or avoid certain punishments) that are pegged at AGI levels. Related tax benefits include those related to medical expenses, passive losses, and taxable Social Security income. In addition, non-itemizers benefit from the charitable contribution deduction to offset the IRA distribution.

In many cases, advance planning can minimize or even eliminate taxes on qualified plan distributions. Often, situations arise in which a taxpayer’s income is abnormally low due to losses, extraordinary deductions, or other factors, meaning that taking more than the minimum in a given year can be beneficial. This is true even for those who do not need to file a tax return but who can increase their distributions and still avoid owing any tax.

Beneficiaries – One important issue is naming beneficiaries to your retirement accounts and keeping them current. It is easy to forget to make beneficiary changes due to death, divorce, or other reasons. A good example is that you might not want your ex-spouse getting your retirement account funds.

When someone inherits a qualified plan or an IRA, he or she must generally begin taking RMDs no later than December 31 of the year following the owner’s death.

If you have questions related to RMDs or are a beneficiary of a retirement plan and need to determine your distribution options, please give this office a call.Share this article…

Crowdfunding Can Have Unexpected Tax Consequences

Crowdfunding Can Have Unexpected Tax Consequences